Refactoring to design patterns - Example of Chain Of Responsibility

Design patterns are great for creating maintainable and reusable code, and, while being universally applicable, they lend themselves well to be implemented in languages that support OOP like Java. This is because these patterns are usually defined in terms of specific “collaborators” that can be very well modelled as interfaces and/or classes, so, it’s easier to “see the patterns” in front of you when using a language that naturally lends itself to it. They are, in essence, a proven and tried way to tackle a problem in software design that has a solution that is proven to be good, robust and generally accepted as a standardized way to solve that specific problem.

In all honesty, I personally think, that design patterns are learnt at a very early stage in one’s education, where there hasn’t been enough exposure to professional codebases and different domains and even companies in order to be able to spot the patterns and decide when they can best be applied. The examples taught in school are usually very self-contained and the “business domain” is tailored very specifically to the individual patterns, to make it easy to “see them”, but, obviously in the real world that is rarely the case. Domains are usually much broader and much more complex than textbook examples, and, over time, as the code evolves, requirements change and the structure of the underlying code resembles more quicksand than a rock solid foundation - with all the moving parts, all the time, it becomes very difficult to see patterns, so, applying them is even harder.

Not done here

The whole “not invented here” syndrome, i.e. the tendency to avoid using or buying products, research, standards, or knowledge from external origins, can be very easily mapped into what I like to call the “not done here” syndrome for applying design patterns.

It feels to me that, while most product-based companies will usually rely on one (or more) frameworks and abstractions like Springboot, Angular, Vaadin, in order to improve the quality and throughput of the code that their business depends on, software teams at these companies usually tend to “coast” along these frameworks, which, in turn, can make the talks around architecture and maintainability and code quality to be proxied through these frameworks: there’s certain patterns in Springboot that are usually followed, dependency injection, abstracting persistency layers with repository interfaces, services passing their dependencies through constructor injection, etc. There will be similar patterns and discussions for Angular and other frameworks. This makes it extra hard to spot where design patterns emerge and when to apply them, and, if your total professional experience amounts to only this type of exposure, it will be even harder to do so. But… there are cases that offer fertile ground for improvements. Let’s look at an example where the Chain of Responsibility pattern fits like a glove.

The symptoms

As described before, design patterns are a way to encode a solution that can be applied to a class of problems. Usually, the way these specific software designs surface in front of us as problems is very subtle, and, over time, it’s usually “impossible” to even “see it” as a problem, until its symptoms become too heavy to be ignored, and then, we need to know what we are looking at to know to which patterns we can map the symptoms so we can apply the “textbook solution”.

Essentially, the context for the application of the Chain Of Responsibility pattern manifested itself under the following scenario:

Imagine you are doing a complete revamp of your authorization mechanism to support a great new auth provider available in the market. You spend several weeks with your team refining several tickets, detailing lots of your complex business logic and preparing yourself for edge cases and special client requests that can arise, devise a new data model, etc.

Once the complexity of preparing the changes is done, you start working on your ticket and it can be dissected in the following way: there are usernames, email addresses and a backup internal DB storing original authorizations for backwards compatibility while this new auth provider isn’t fully in place. The basis of the auth mechanism is the following:

- assume that there is always information available for a given username; (lets imagine this is StepOneService)

- when this is not true, attempt to use the email address; (this is StepTwoService)

- if all else fails, just query the backup DB; (and FinalService)

Obviously, since there has to be a pass-through and fallback mechanism through each of these services, we need supporting Repository interfaces as well as CollaboratorService classes, to wire all the logic together.

Now, this logic needs to be implemented in code, and, as you can imagine, there is a myriad of details in each of these steps that need to be handled carefully and properly and each stage needs to be extremely well-tested and of course, we need integration tests for the entire flow to ensure that the pieces are structurally sound and link well together. Let’s take a first stab at this with using Java and Springboot.

Since we are using Springboot as this auth will be exposed via a new endpoint, the first approach we can take is something along the lines of:

TopLevelService(StepOneService usernameInfoService, CollaboratorStepOne collaborator, StepTwoService emailService, CollaboratorStepTwo otherCollaborator, FinalService finalService, BackupDbRepository repository) {

this.usernameInfoService = usernameInfoService;

this.collaborator = collaborator;

this.emailService = emailService;

this.otherCollaborator = otherCollaborator;

this.finalService = finalService;

this.repository = repository;

}

I would wager that this type of structure for a top level service would not be too unsual to see in a production codebase, especially when one starts by, for instance, implementing only the happy flow through the system and then handle the details for each fallback as the other paths through the service. While this type of code is acceptable and it can even be a good approach to take for simple scenarios, the first symptoms that some things are “off” here, are the following:

-

complex logic on the

topLevelService: even if each individual service does one thing in encapsulation and does it well, this doesn’t discard the fact that there are simply too many collaborators on this top level service. This pain point is best felt when attempting to unit test this service. How hard is this? Each unit test needs to be very specifically tailored to handle each possible path both through and out of, each individual service. Then the collaborators need to be mocked as well with very specific conditions to ensure that each service can be tested for all possible scenarios. Even dozens of tests can’t give us a big assurance of correctness for all of this. This feels hard to grasp because each small service in isolation does just one thing, but the complex chain interactions make the complexity explode, and, if we encapsulated the collaborators inside each service, the complexity would be shifted around, because of the next point; -

collaborators can force the existence of several potential exit points, which indirectly creates many if-else branches for the logic to follow through for each dedicated service when assembling it all in this top level service. Definitely hard to test and maintain;

-

code becomes too procedural and rigid: when keeping all the services aggregated at a top level service, the response needs to be assembled, but, that can only happen once the whole business logic has executed so it can be passed to other collaborators. So that’s an extra complexity step to deal with. And it’s all in a single place;

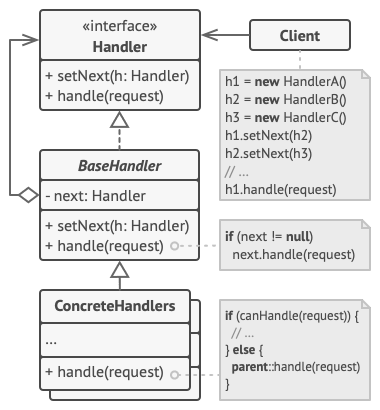

Refactoring to the Chain of Responsibility Pattern

The big idea that can make us untangle this complex top level service, is that of a chain of responsibilities: each service will be responsible for doing only two things:

-

either produce a response (as a standalone service together with its single collaborators injected as dependencies in the constructor)

-

or, conclude that it can’t produce a response for whatever reason (eg. an exception was thrown, there is no data in the DB for a username, invalid email, invalid input, etc) and in that scenario, it should simply pass the responsibility to the next service in the chain until either:

a) a response is built using one of the services in the chain; b) all the services in the chain were “exhausted” so we simply call the last one that goes to the backup DB;

Like this we can have a much more simplified top level service, where only the services that compose this chain are defined:

List services = asList( usernameInfoService, emailService, finalService);

TopLevelService(services) {

this.services = services;

}

For implementing the chain of responsibility pattern in code, we can make each service implement an interface as follows:

public interface AuthHandler {

boolean canHandleRequest(String input);

public AuthData handleRequest(String input, @AuthenticationPrincipal UsernamePasswordToken token);

}

Now each service will implement this interface so, a scaffolding example of StepOneService could be:

public class StepOneService implements AuthHandler, Ordered {

//assume constructor and collaborator services injected

@Override

public boolean canHandleRequest(String input) {

//Business logic example to determine if serviceOne can process request

if(collaboratorOne.parseInput(input) && repository.exists(input)){

return true;

}

else {

return false;

}

}

}

@Override

public AuthData handleRequest(String input, @AuthenticationPrincipal UsernamePasswordToken token){

if(canHandleRequest(input)){

//actually retrieve the data and build the response

}

else {

// The next service in the chain can be injected as a collaborator and if this current service cant handle it, we pass it along to the next one in the chain

return nextService.handleRequest(...);

}

@Override

public int getOrder(){

return 1;

}

The method getOrder defined above comes from Springboot Ordered interface and defines the order of this service in the chain.

Finally, to wrap up, in Springboot, all these services which compose the chain, could be injected as a list of services in the top level one as seen above:

List<AuthHandler> services = asList( usernameInfoService, emailService, finalService);

TopLevelService(services) {

this.services = services;

}

Note how we can use the interface to wire together in the top level service all the correct collaborator services which will be invoked in the order as defined in the Ordered interface.

Like this we can test each of these services in isolation, mock their collaborators and have a much leaner and clean top level service.

Design patterns can be hard to see and spot, but, when used in the right context they can leverage OO patterns to make your code easier to follow, read and maintain. A final important remark is that the patterns usually need to be slightly adjusted to map the way certain frameworks require developers to structure their code, but, as long as the basic underlying principles are understood, they can be leveraged to the fullest.